We end our week enjoying Tahitian music and dance with by meeting Toa’Ura (“Red Warriors,”) a multifaceted Tahitian ensemble that fuses traditional Polynesian percussion and melodies with contemporary Western instruments and song structures. To get a sense of how this works -–and it works very well — you can watch many Toa’Ura videos on YouTube, such as in this video from a live performance, dancers and all. Cheers!

Tag Archives | Tahiti

Ote’as for Everyone

Traditional French Polynesian music works hand in hand with dance to tell a story. The Polynesian percussion vocabulary uses multiple flexible phrases, each of which has a distinct name (Napoko, Toma, second Toma, Pahae, second Pahae, Paea, Puara-Ta, Takoto, Mati, Bora Bora, etc.) to construct the narrative that provides context for the dance. In class we’re going to some of these phrases to develop the narrative of a hip-shaking, grass-skirt-wearing Tahitian dance called an “ote’a.”

The Tahitian ote’a is not a Hawaiian hula; it’s much faster and, purposefully, not nearly as graceful. Music used for ote’as is vocal-free–only drums (to’eres, pahu, etc.) are allowed. Some ote’as are for men only, some for women only, some for all to dance together. For their dances men often choose narrative themes such as sailing or battles. Women often sing of nature or create images from their home lives. In either case, the theme of the ote’a should inform all the moves in the dance.

Tahitian Himene Tarava

When Christian missionaries arrived in French Polynesia several centuries ago, most considered the music as primitive and too seductive in nature; colonial authorities regularly banned much Polynesian music, replacing it with hymns and other forms of “more appropriate” songs. French Polynesians took quickly to Christian music, called “himene” (hymns), and by the early 20th century several types of himene had developed. For example, “himene tarava” features a large choir — up to 80 singers — composed of men and women who sing in complicated multi-part, multi-tone harmonies. According to National Geographic’s writing on the music of Tahiti, “this form of singing…is distinguished by a unique drop in pitch at the end of the phrases, which is a characteristic formed by several different voices; it is also accompanied by steady grunting of staccato, nonsensical syllables.”

Make your own Pahu

Want to make your own Tahitian Pahu drum to use in your Tahitian drumming ensemble? It’s easy! Just follow the step-by-step instructions included in this 11 part YouTube series. All you have to do is cut down one of your local coconut trees, chop out a drum-sized chunk, remove the bark with a stick, scrape the outer bark off the stump with a slightly angled draw-knife, spend a couple days with a Japanese spear point plane and a half dozen other tools to get at the next layer…okay, so it’s not so easy.

Drumming at Tahiti Fete

Polynesian drumming ensembles, such as those from Tahiti — like the one in this video — are composed of multiple drums of different sizes and pitches, all of which are made from materials found nearby. A drumming group will often feature instruments such as the sharply pitched to’ere, pronounced “to-eddie,” which is a narrow cylindrical drum made from a hollowed-out log and hit with a wood stick and the more resonant pahu, such as the Tahitian bass pahu, which drummers hit with padded sticks.

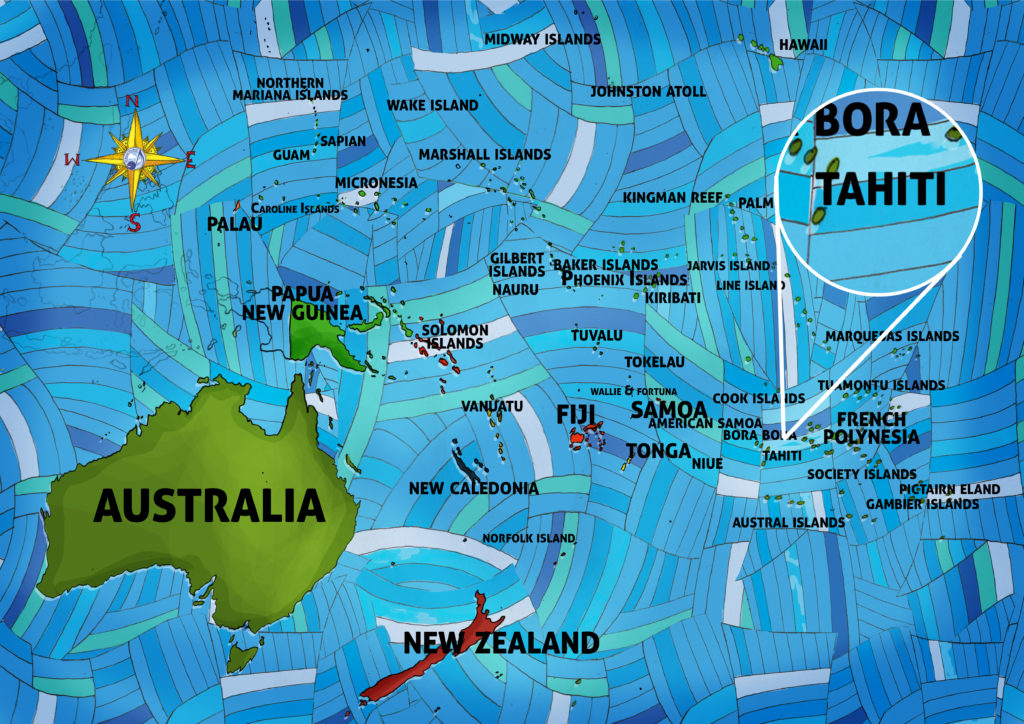

In Polynesia We Navigate Thousands of Miles Across the Seas

This week our online classes finally take us to Polynesia — yay Melanesia!, yay Micronesia!, but super-yay to the thousands of glorious islands of Polynesia! This week we specifically land in French Polynesia, and, even more specifically, in the French Polynesian nation of Tahiti. The first inhabitants of Tahiti arrived between about 300 and 800 CE, having traveled thousands of miles across the Pacific from other island groups, mostly Polynesian ones, like Samoa and Tonga. As on many Polynesian islands, Tahitian society is organized based upon a complex interplay of chiefdoms, clans and the power dynamics between them. In Tahiti, clan leaders were powerful but not all-powerful; they generally made decisions in consultation with general assemblies. Tahitian culture had a strong oral tradition involving an extensive mythology based on tales about various gods, as well as extensive traditions surrounding tattooing and navigation. Tahitians opposed colonization byt the French for centuries, supporting a strong succession of kings from Pōmare line. In 1880 the French forced Pōmare V, to abdicate the throne. In 1946 France made all of French Polynesia an “overseas territory” and granted Tahitians French citizenship. In 2003 French Polynesia became an “overseas collectivity” and in 2004 it transformed into “an overseas country.”

In Tahiti Our Hands are the Wind

This week’s class theme of “dancing with our hands” takes us to the Pacific, where dancers all over the region use their hands to tell tales from the natural world. In this video of a Tahitian song, “Te Pua Noanoa,” dancers use flowing arm and hand motions to celebrate the motion of the wind and waves.

“Te Pua Noanoa” is Tahitian song written by Heremoana Ma’ama’atuaiahutapu about two women who string together flowers to make necklaces known in Tahitian as “heis” (in Hawaiian, “leis.”) Though our Tahitian dancing leaves a lot to be desired, when we sing “Te Pua Noanoa” in class we sound lovely.